### Highlights

- Common sense tells us: if a learner goes to school and studies diligently, they will succeed in life. This belief underpins the promise of school education as a pathway to social and economic mobility, yet it masks the many contradictions and shortcomings of the system

- Schools reproduce social and cultural inequalities and invisibilise birth-based advantages and, in some cases, reinforce birthbased disadvantages. In the words of the French sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu: “The educational system, an institutionalised classifier... transforms social classifications into academic classifications, with every appearance of neutrality.”

- They did not need to prepare meticulously; they walked onto the stage and stole the show. I remember students from a school adjacent to mine, one that “catered to poorer segments of society”, and they occasionally turned up for some of these debates. The fact that their English seemed laboured, their speeches on stage reflecting days and nights of preparation, immediately put off the judges. My peers and I almost always walked away with the win. Many years later, and many interventions to common sense notwithstanding, Bourdieu’s notion that the perception of success is very much a factor of the structural location of the perceiver rings true in my ears.

- As “everybody” gets qualified, dominant educational institutions move to other criteria—ease, style, and other such embodiments of caste and class—to continue to ensure the reproduction of their domination. As other caste and class groups, historically marginalised for centuries, enter the school education fold, a variety of linguistic, epistemic, and material tools are employed to perpetuate the distinction between social groups.

- what a school does, how it is supposed to function, how schools can subvert exploitative relationships, whether access to schooling is enough, and what quality education means, do not feature in political discourse. The school, its purposes, and its stakeholders continue to be taken for granted.

- What we have seen for decades now is a tragic relegation of school education as primarily a subject of implementation science, left to the bureaucracy. This shift takes away school education from what it is, a profoundly political question. This relegation takes the institutional framework of a school as a constraint, and subsequently turns questions of school education into input/output questions.

- Education, in this model, is treated as a technical or managerial problem to be optimised for efficiency, rather than as a foundational site for shaping democratic values, addressing social inequalities, or imagining more just futures.

- Many spirited debates between practitioners of education and theorists often fall into a familiar tailspin. The practitioner says: “You theorists keep complaining and critiquing; what are you doing to change the system?” The theorist says: “You practitioners don’t look at the bigger picture, and reproduce old problems in new ways.” This debate is but another manifestation of the inherent contradictions of education, and we seem to be lacking the appropriate tools to tackle this contradiction

- In his 1869 speech titled “On General Education”, Karl Marx pointed out that “there was a peculiar difficulty connected with this question. On the one hand, a change of social circumstances was required to establish a proper system of education; on the other hand, a proper system of education was required to bring about a change of social circumstances; we must therefore commence where we are.”

---

### Let’s go back to school

### Treating education as mere management hides its real role: schools shape citizens, society, and democracy itself.

Published: Aug 26, 2025 15:31 IST - 12 MINS READ

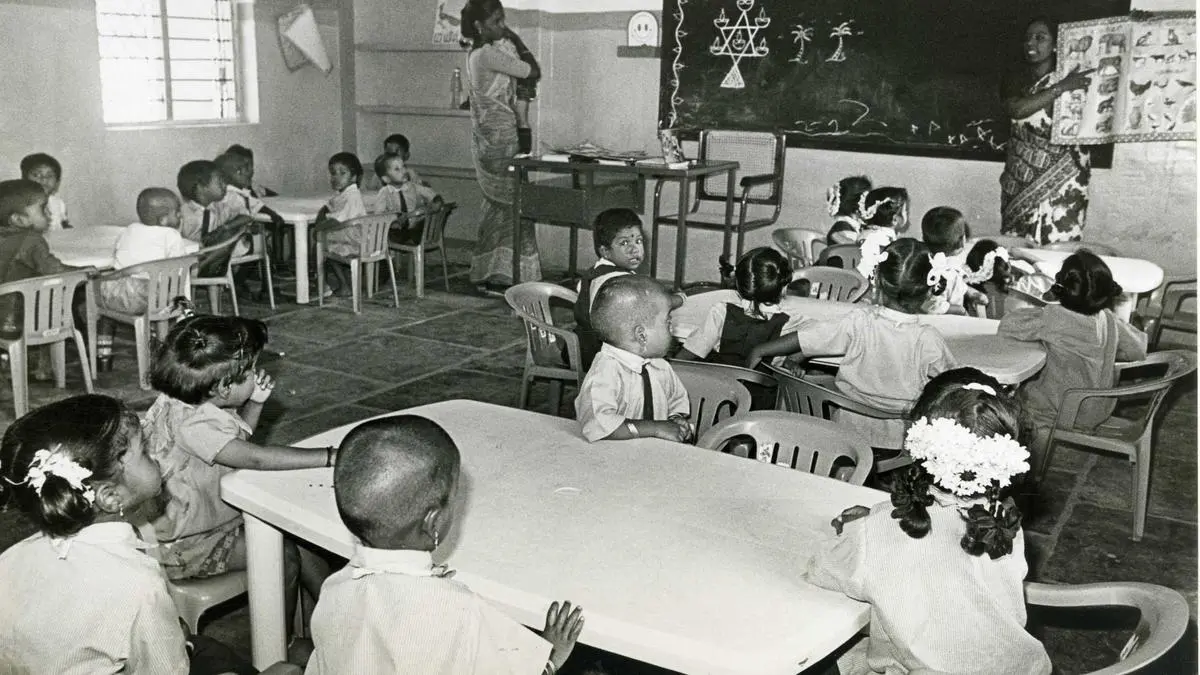

At a corporation kindergarten school in Tiruvanmiyur, Chennai, on August 20, 1997. | Photo Credit: K. Pichumani

The purpose of critical thought—and, by extension, truth-seeking—is to challenge what we accept as common sense. Common sense tells us: if a learner goes to school and studies diligently, they will succeed in life. This belief underpins the promise of school [education](https://frontline.thehindu.com/the-nation/education/india-education-higher-education-universities-rajiv-gandhi-cbse-bjp-nda-demonetisation-liberal-arts/article68972184.ece) as a pathway to social and economic mobility, yet it masks the many contradictions and shortcomings of the system. In my experience as a teacher and researcher, I have often seen the assumption that simply gaining access to school removes the most significant barrier to achievement. While this assumption is partly true, it is also incomplete. Moreover, this assumption masks several vital questions. What is the purpose of school education? More pointedly, who stands to benefit most from it?

What does a school do? At first thought, many answers come to mind. It is a space for learning and teaching, a space for students to become moral citizens, a space for building human capital so that learners can acquire skills that they can then use to get jobs, and a space to obtain credentials.

Beyond these visions, schools also serve less visible and powerful functions. Schools reproduce social and cultural inequalities and invisibilise birth-based advantages and, in some cases, reinforce birth-based disadvantages. In the words of the French sociologist, Pierre Bourdieu: “The educational system, an institutionalised classifier… transforms social classifications into academic classifications, with every appearance of neutrality.”

Despite this reality, the ideology of meritocracy claims that it does not matter if you are born into the highest echelons of privileged-caste, upper-class households or in a poor, oppressed-caste household; what matters is that you go to school and study hard. Schools, thus, become the foremost institutions for the propagation of formal equality, a [liberal dream](https://frontline.thehindu.com/the-nation/education/india-ivy-league-education-crisis/article69700493.ece). But the liberal dream of formal equality in deeply stratified societies like India is an illusion to mask the enormous caste- and class-based differences present in society and, more importantly, to legitimise birth-based advantages as educational ones. Bourdieu, across various writings, underlines a series of powerful mechanisms through which the school does not allow for the social or economic mobility of the disadvantaged.

**Also Read | [Why a third of India’s 716 Eklavya Model Schools for tribal children remains ‘non-functional’](https://frontline.thehindu.com/the-nation/education/tribal-education-crisis-eklavya-schools-pvtg-enrollment-drops/article69071794.ece)**

To begin with, underprivileged learners tend to have lower success rates due to multiple structural barriers that hinder their progress. According to Bourdieu, societal expectations are adjusted in response, leading to a misrecognition that underprivileged learners are inherently less capable of succeeding both in and out of school. As a result, common sense dictates that these outcomes are natural and inevitable. This belief has a powerful side effect: it reinforces values, behaviours, and forms of knowledge associated with the dominant (privileged) group as the “norm” or standard within educational institutions. For example, if speaking [English](https://frontline.thehindu.com/social-issues/gender/desperation-of-punjabi-youth-to-settle-abroad-is-fuelling-marriages-with-top-ielts-scoring-women/article68604978.ece) fluently is seen as a sign of intelligence or capability, and privileged students speaking it appears “natural”, then English, and the culture associated with it, becomes the default or “natural” culture of the school. Other ways of speaking, learning, or being are viewed as lesser or as something to be overcome.

However, every story of disenfranchisement and disadvantage has exceptions. Even when a learner overcomes some structural barriers and achieves success, subsequently, they often face fewer and different opportunities compared with more privileged students. Disadvantaged learners and their families, then, tend to make choices that may not necessarily help them capitalise on the initial advantages, and in fact, they often opt out of the very system that gave them the initial success. This, within privileged discourses—which ultimately determine what common sense is—is seen as them making “wrong” choices.

Students studying outdoors at a government school in Krishnagiri, Tamil Nadu, when the classrooms were locked to safeguard the bicycles and laptops meant for distribution to students by the government, on August 11, 2015. | Photo Credit: N. Bashkaran

One part of my research looks at extracurricular activities, particularly public-speaking competitions in elite private schools in a south Indian city, and I found that not only did these schools insist on English as the primary medium of competition but also intentionally invited educational institutions where learners predominantly spoke English. If learners were to partake in regional languages, they faced immediate disqualification. Thus, many schools deliberately did not send their students to take part in these competitions, a “wrong” choice. Later, some of these elite private schools became “upset” by the lack of response from the schools that catered to underprivileged learners and stopped inviting them altogether.

Through this, I saw that homogeneity in these schools increased. Students became more like each other and had fewer causes or opportunities to question the “neutrality” or “naturalness” of their order. As Bourdieu puts it: “These structures of relationship serve to transform social advantages or disadvantages into educational ones through choices which are linked to social origins.”

Now, let us imagine an underprivileged learner somehow passed through all these barriers. Further hurdles remain. Bourdieu found that schools often devalue their own culture “by denigrating a piece of work as too academic”. That is, it carries “the vulgar mark of effort” and not the appearance of “ease and grace”. Growing up, I studied in a school where students were exactly like me—Brahmin, parents identified as “middle class”, most in service-sector professions. My school encouraged me to participate in plenty of debates, and many of my peers, some of whom I looked up to, debated with a natural flair.

Students writing their high school final examination in Dimapur, Nagaland, on February 15, 2017. | Photo Credit: PTI

They did not need to prepare meticulously; they walked onto the stage and stole the show. I remember students from a school adjacent to mine, one that “catered to poorer segments of society”, and they occasionally turned up for some of these debates. The fact that their English seemed laboured, their speeches on stage reflecting days and nights of preparation, immediately put off the judges. My peers and I almost always walked away with the win. Many years later, and many interventions to common sense notwithstanding, Bourdieu’s notion that the perception of success is very much a factor of the structural location of the perceiver rings true in my ears.

### Privileged castes and their symbolic power

In India’s caste-based society, schools tend to advantage or disadvantage their learners on the basis of their structural location. The privileged castes can exercise *symbolic power,* the power to determine what is legitimate and what is not. Through the lens of an educational system that tends to obscure birth-based advantages as educational ones, the privileged castes view the established structural order not as arbitrary or socially constructed but as a self-evident and natural order. An order that corresponds to common sense.

Something remarkable has happened in Indian school education over the past two decades. India has achieved a 100 per cent Gross Enrolment Ratio in primaryschools. That is, every child in India attends school, a phenomenal achievement and a testament to the Indian state’s capacity to do well for its citizens —if it so wishes to. There is, however, a consequence of this achievement. As more people access education, there comes a devaluation of the credentials that come with schooling.

As “everybody” gets qualified, dominant educational institutions move to other criteria—ease, style, and other such embodiments of caste and class—to continue to ensure the reproduction of their domination. As other caste and class groups, historically marginalised for centuries, enter the school education fold, a variety of linguistic, epistemic, and material tools are employed to perpetuate the distinction between social groups.

For example, some of the private schools in my study arbitrarily changed their minimum eligibility criteria for admission to a minimum family income of Rs.10 lakh. They justified it as the school’s decision to “cater to a particular segment of society”.

Students studying satellite models at a workshop in the Regional Science Centre in Tirupati, Andhra Pradesh, on July 18, 2025. | Photo Credit: K.V. Poornachandra Kumar

Thus far, I have tried to detail some mechanisms through which the school functions as an institution that reproduces advantages and distinctions. However, the promise of the school as an engine for social and economic mobility is salient as well. How then do we think of the school in relation to society? What is the purpose of education, and how do we think of it as a tool for justice?

The school is here to stay. As a society, we have not yet imagined another technology or institution that can bring hundreds of learners together into a shared space, engage them for 7 to 8 hours a day, 5 to 6 days a week, for 12 to 15 years. Yet, what a school does, how it is supposed to function, how schools can subvert exploitative relationships, whether access to schooling is enough, and what quality education means, do not feature in political discourse. The school, its purposes, and its stakeholders continue to be taken for granted.

What we have seen for decades now is a tragic relegation of school education as primarily a subject of implementation science, left to the bureaucracy. This shift takes away school education from what it is, a profoundly political question. This relegation takes the institutional framework of a school as a constraint, and subsequently turns questions of school education into input/output questions. For example, what would be the effect on learning outcomes if we equip a set of schools with computers? How would teacher motivation levels increase if we eased some data-entry burden? Would a learner’s arithmetic level improve if we made a specific pedagogical intervention? These are important questions, and as some of my fellow contributors highlight, some brilliant work is happening to tackle these questions. But the point remains that the discourse around school education remains largely technocratic.

This is not a phenomenon isolated to India. The pressing questions of what, why, and for whom education exists are no longer seen as matters for collective deliberation or civic engagement but instead are delegated to “educationalists”—a specialised class of administrators and technical experts. Education, in this model, is treated as a technical or managerial problem to be optimised for efficiency, rather than as a foundational site for shaping democratic values, addressing social inequalities, or imagining more just futures.

This manoeuvre was useful because, as the education theorist Houman Harouni notes, it allowed educators, learners, parents, and families to overlook fundamental contradictions in educational practice. Some of the contradictions require serious deliberation; we must uphold schooling as a social good while also acknowledging that schools can be deeply oppressive institutions.

This is not to say that the marginalised and underprivileged are devoid of agency; that, like all other social institutions, the school locks them into cycles of oppression. Recent sociological perspectives point out that thinking of schools (or any social institution) as only sites of social reproduction are incorrect. As the sociologist of education Amman Madan points out: “\[S\]chools are better seen as places where tugs of war are taking place than as machines that turn out automatons. They are sites of resistances and oppositions.” My fellow contributors in this special issue speak to this dynamic in a multitude of ways.

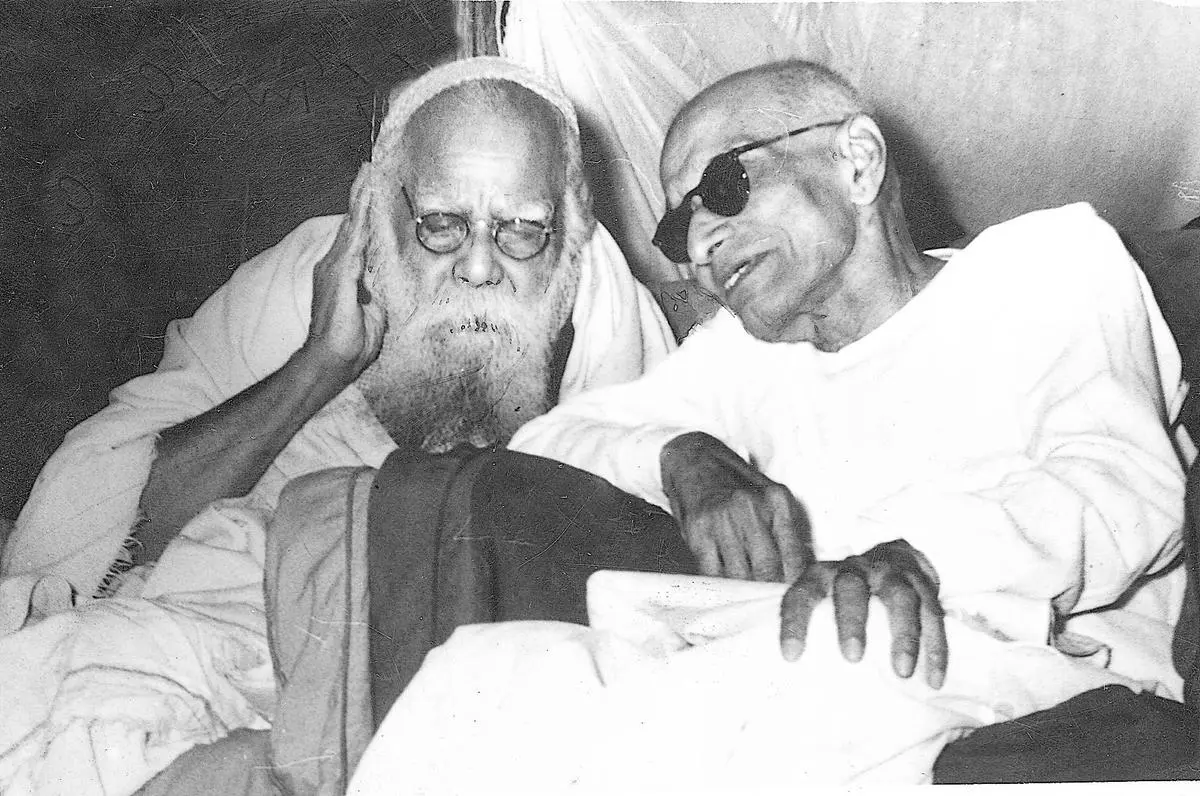

E.V. Ramasamy “Periyar” and C. Rajagopalachari at the Prophet’s Day meeting held in Madras on December 12, 1953. | Photo Credit: THE HINDU ARCHIVES

Reflecting on what social justice entails, the American philosopher Nancy Fraser states: “We must evaluate social arrangements not on the ‘goodness’ or ‘badness’ of society, but from the perspective of how fair or unfair are the terms of interaction that are institutionalised in society.” In this view, justice pertains to social structures and institutional frameworks and not just to daily social interactions between people.

If the school is an institution for social justice, we must ask whether society’s structures and institutions allow all to participate as peers in social interaction. The scientific practice of education alone cannot answer this question; it requires serious political deliberation.

### School education as emancipatory tool

Dr B.R. Ambedkar and “Periyar” E.V. Ramasamy’s thoughts on education can be contextualised with the above question, whether institutions of education allow all to participate as peers. They both recognised school education as an emancipatory tool, but in its form then (and now), the institutional framework was inherently unfair to the marginalised. Their unequivocal and tireless push for affirmative action can be seen as a way to make the institutional frameworks of education fairer. Similarly, Periyar’s firm resistance to C. Rajagopalachari’s *Kula Kalvi Thittam* (hereditary education scheme) was resistance to using schooling as an institutional framework to maintain status inequality.

Education as a scientific practice, despite all its merits, must view its beneficiaries as objects who require different inputs. When tuned right, it can provide desirable outputs. It forces itself to approach schooling in isolation from society. But a learner only spends 7-8 hours a day inside the enclosure called a school. The remaining 16-17 hours are spent outside, in the community, at home. These are spaces of learning as well. Schools are not isolated from societal interactions; they shape and are shaped by them.

This takes me back to my original lament: How, then, is schooling not a salient feature of our elections? How have we taken schooling for granted for so long?

**Also Read | [Hindutvaisation of education: Narendra Modi-led government's game plan under NEP](https://frontline.thehindu.com/cover-story/hindutvaisation-of-education-narendra-modi-led-governments-game-plan-under-nep/article38483351.ece)**

Many spirited debates between practitioners of education and theorists often fall into a familiar tailspin. The practitioner says: “You theorists keep complaining and critiquing; what are you doing to change the system?” The theorist says: “You practitioners don’t look at the bigger picture, and reproduce old problems in new ways.” This debate is but another manifestation of the inherent contradictions of education, and we seem to be lacking the appropriate tools to tackle this contradiction.

In his 1869 speech titled “On General Education”, Karl Marx pointed out that “there was a peculiar difficulty connected with this question. On the one hand, a change of social circumstances was required to establish a proper system of education; on the other hand, a proper system of education was required to bring about a change of social circumstances; we must therefore commence where we are.”

To commence where we are, we ought to treat common sense as our collective enemy. We ought to discuss education widely and deeply, at our dining tables, workplaces, WhatsApp groups, election campaigns, legislative Assemblies and parliaments. This special issue is one intervention towards that end.

*Vishal Vasanthakumar is currently enrolled for a PhD in sociology at the University of Cambridge as a Gates Cambridge Scholar.*

## Featured Comment

Good article 👍

"The teacher must be at the centre of the fundamental reforms in the education system. {Refer to the Introduction of NEP2020}"

- NO NO NO, it should be the STUDENT at the centre of the fundamental reforms in the education system and other stakeholders – like the teachers, Universities, School boards, parents, etc. – at the periphery to make these reforms possible, as strong support systems.

**Destiny of the children and subsequently that of the society is initiated in a classroom...**

...challenging, when the politicians play with the education system and majority (not all) of the teaching fraternity is either thinking of pay-scale salaries or worried about the CHB pays. We never go on strike for our students but always for salaries.

Commented by Ujjwala

## Featured Comment

Good article 👍

"The teacher must be at the centre of the fundamental reforms in the education system. {Refer to the Introduction of NEP2020}"

- NO NO NO, it should be the STUDENT at the centre of the fundamental reforms in the education system and other stakeholders – like the teachers, Universities, School boards, parents, etc. – at the periphery to make these reforms possible, as strong support systems.

**Destiny of the children and subsequently that of the society is initiated in a classroom...**

...challenging, when the politicians play with the education system and majority (not all) of the teaching fraternity is either thinking of pay-scale salaries or worried about the CHB pays. We never go on strike for our students but always for salaries.

Commented by Ujjwala

### The century of self-respect

[](https://frontline.thehindu.com/social-issues/social-justice/periyarism-homebound-caste-oppression/article70120622.ece)

### Editor’s note: The other freedom fight

[\+ SEE all Stories](https://frontline.thehindu.com/current-issue/)

Looks like you are already logged in from more than 5 devices!

To continue logging in, remove at least one device from the below list

[Terms & conditions](https://www.thehindugroup.com/privacy.html) | [Institutional Subscriber](https://forms.office.com/r/tz7UETzxUs)